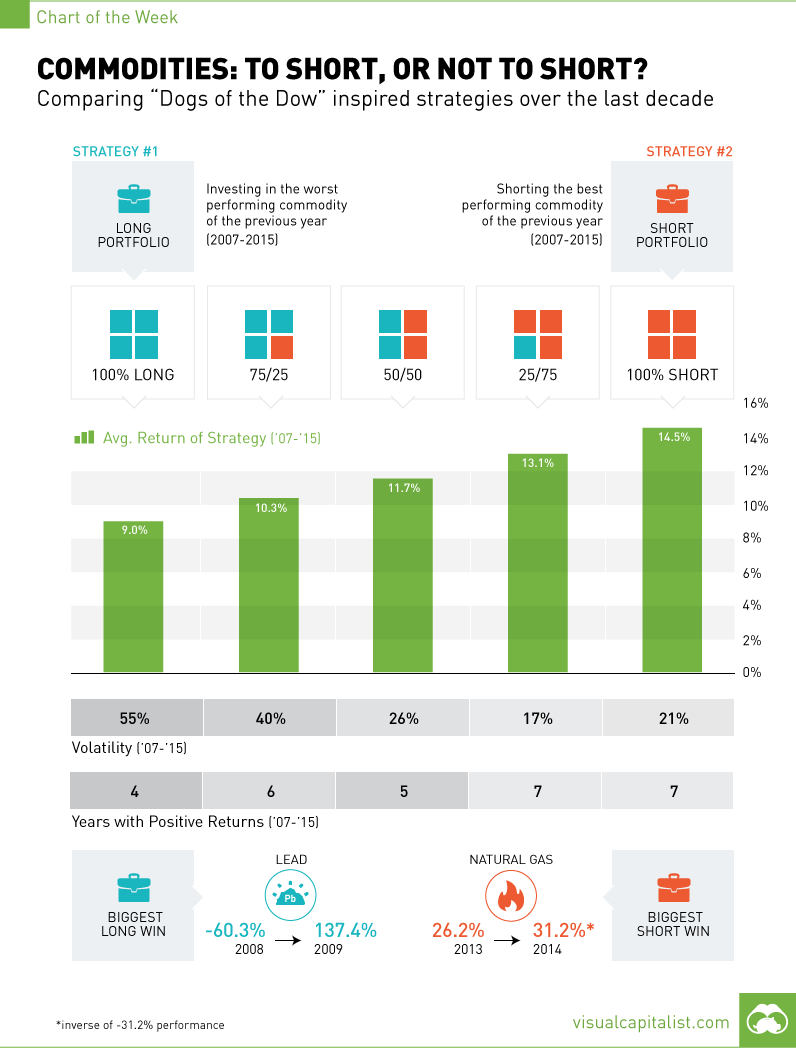

Commodities: To Short, or Not to Short? [Chart]

Comparing “Dogs of the Dow” inspired strategies over the last decade

The Chart of the Week is a weekly Visual Capitalist feature on Fridays. Over the last week, we have received a wide variety of reactions from our audience regarding the Periodic Table of Commodity Returns that we published last Thursday from our friends at U.S. Global Investors. The most interesting email came from Brad Farquhar, the Executive Vice President and CFO of Input Capital, a Canadian-based agricultural streaming company. In his email, Brad attached a chart summarizing the cumulative returns using a long/short commodity strategy where he imagined going long on the worst performing commodity of the previous year, while shorting the best performing commodity. For example, the long-only portfolio would have invested in natural gas in 2007, because gas was the worst performing commodity in 2006 with a -43.9% return. The short-only strategy would have shorted nickel in 2007 (betting that nickel would drop in price) because it was the best performer of 2007 with 145.5% returns. On a cumulative basis (re-investing money from each year), the long-only strategy returned -0.9% compound annualized growth between 2007 and 2015, while the short-only strategy brought in 12.4% annualized returns. A 50/50 hybrid (50% long, and 50% short) gave us the equivalent of 9.6% returns each year.

Our Variation

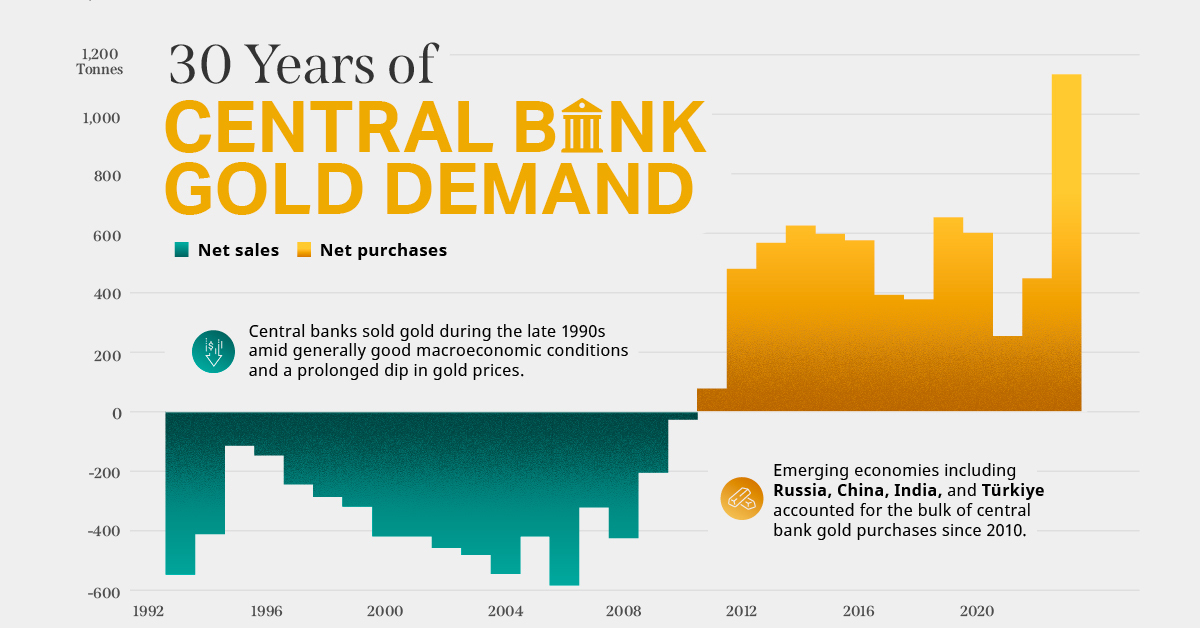

Inspired by Brad’s analysis, we did our own variation of this “Dogs of the Dow” type of exercise to look at these long and short commodity portfolios in a slightly different light. We analyzed five portfolios (100% long, 75% long, 50% long/short, 75% short, and 100% short) for the average annual return, volatility, and number of years with positive returns. Here’s the results: The best performing portfolio was 100% short, with an average annual return of 14.5%. The 75% short portfolio had nearly as good of returns at 13.1%, with the lowest volatility (using standard deviation) at +/- 17%. Both the 100% short and 75% short portfolios provided positive returns in 7 of the last 9 years. Meanwhile, going long was much more risky. A 100% long portfolio had gains in only 4 of 9 years, with a huge standard deviation of +/- 55%. Over the time period in question, energy commodities killed portfolios with “long” exposure. In 2011 and in 2015, the worst performer of the previous year (natural gas and oil respectively) was also the worst performer the following year, creating terrible returns for the long-heavy portfolios. Oil, for example, was down -45.6% in 2014 and then was also down -30.5% in 2015. Not a very effective strategy. What will be a better trade in 2016: shorting the best performing commodity of last year (lead), or going long on nickel, the worst performer of 2015? on Did you know that nearly one-fifth of all the gold ever mined is held by central banks? Besides investors and jewelry consumers, central banks are a major source of gold demand. In fact, in 2022, central banks snapped up gold at the fastest pace since 1967. However, the record gold purchases of 2022 are in stark contrast to the 1990s and early 2000s, when central banks were net sellers of gold. The above infographic uses data from the World Gold Council to show 30 years of central bank gold demand, highlighting how official attitudes toward gold have changed in the last 30 years.

Why Do Central Banks Buy Gold?

Gold plays an important role in the financial reserves of numerous nations. Here are three of the reasons why central banks hold gold:

Balancing foreign exchange reserves Central banks have long held gold as part of their reserves to manage risk from currency holdings and to promote stability during economic turmoil. Hedging against fiat currencies Gold offers a hedge against the eroding purchasing power of currencies (mainly the U.S. dollar) due to inflation. Diversifying portfolios Gold has an inverse correlation with the U.S. dollar. When the dollar falls in value, gold prices tend to rise, protecting central banks from volatility. The Switch from Selling to Buying In the 1990s and early 2000s, central banks were net sellers of gold. There were several reasons behind the selling, including good macroeconomic conditions and a downward trend in gold prices. Due to strong economic growth, gold’s safe-haven properties were less valuable, and low returns made it unattractive as an investment. Central bank attitudes toward gold started changing following the 1997 Asian financial crisis and then later, the 2007–08 financial crisis. Since 2010, central banks have been net buyers of gold on an annual basis. Here’s a look at the 10 largest official buyers of gold from the end of 1999 to end of 2021: Rank CountryAmount of Gold Bought (tonnes)% of All Buying #1🇷🇺 Russia 1,88828% #2🇨🇳 China 1,55223% #3🇹🇷 Türkiye 5418% #4🇮🇳 India 3956% #5🇰🇿 Kazakhstan 3455% #6🇺🇿 Uzbekistan 3115% #7🇸🇦 Saudi Arabia 1803% #8🇹🇭 Thailand 1682% #9🇵🇱 Poland1282% #10🇲🇽 Mexico 1152% Total5,62384% Source: IMF The top 10 official buyers of gold between end-1999 and end-2021 represent 84% of all the gold bought by central banks during this period. Russia and China—arguably the United States’ top geopolitical rivals—have been the largest gold buyers over the last two decades. Russia, in particular, accelerated its gold purchases after being hit by Western sanctions following its annexation of Crimea in 2014. Interestingly, the majority of nations on the above list are emerging economies. These countries have likely been stockpiling gold to hedge against financial and geopolitical risks affecting currencies, primarily the U.S. dollar. Meanwhile, European nations including Switzerland, France, Netherlands, and the UK were the largest sellers of gold between 1999 and 2021, under the Central Bank Gold Agreement (CBGA) framework. Which Central Banks Bought Gold in 2022? In 2022, central banks bought a record 1,136 tonnes of gold, worth around $70 billion. Country2022 Gold Purchases (tonnes)% of Total 🇹🇷 Türkiye14813% 🇨🇳 China 625% 🇪🇬 Egypt 474% 🇶🇦 Qatar333% 🇮🇶 Iraq 343% 🇮🇳 India 333% 🇦🇪 UAE 252% 🇰🇬 Kyrgyzstan 61% 🇹🇯 Tajikistan 40.4% 🇪🇨 Ecuador 30.3% 🌍 Unreported 74165% Total1,136100% Türkiye, experiencing 86% year-over-year inflation as of October 2022, was the largest buyer, adding 148 tonnes to its reserves. China continued its gold-buying spree with 62 tonnes added in the months of November and December, amid rising geopolitical tensions with the United States. Overall, emerging markets continued the trend that started in the 2000s, accounting for the bulk of gold purchases. Meanwhile, a significant two-thirds, or 741 tonnes of official gold purchases were unreported in 2022. According to analysts, unreported gold purchases are likely to have come from countries like China and Russia, who are looking to de-dollarize global trade to circumvent Western sanctions.

There were several reasons behind the selling, including good macroeconomic conditions and a downward trend in gold prices. Due to strong economic growth, gold’s safe-haven properties were less valuable, and low returns made it unattractive as an investment.

Central bank attitudes toward gold started changing following the 1997 Asian financial crisis and then later, the 2007–08 financial crisis. Since 2010, central banks have been net buyers of gold on an annual basis.

Here’s a look at the 10 largest official buyers of gold from the end of 1999 to end of 2021:

Source: IMF

The top 10 official buyers of gold between end-1999 and end-2021 represent 84% of all the gold bought by central banks during this period.

Russia and China—arguably the United States’ top geopolitical rivals—have been the largest gold buyers over the last two decades. Russia, in particular, accelerated its gold purchases after being hit by Western sanctions following its annexation of Crimea in 2014.

Interestingly, the majority of nations on the above list are emerging economies. These countries have likely been stockpiling gold to hedge against financial and geopolitical risks affecting currencies, primarily the U.S. dollar.

Meanwhile, European nations including Switzerland, France, Netherlands, and the UK were the largest sellers of gold between 1999 and 2021, under the Central Bank Gold Agreement (CBGA) framework.

Which Central Banks Bought Gold in 2022?

In 2022, central banks bought a record 1,136 tonnes of gold, worth around $70 billion. Türkiye, experiencing 86% year-over-year inflation as of October 2022, was the largest buyer, adding 148 tonnes to its reserves. China continued its gold-buying spree with 62 tonnes added in the months of November and December, amid rising geopolitical tensions with the United States. Overall, emerging markets continued the trend that started in the 2000s, accounting for the bulk of gold purchases. Meanwhile, a significant two-thirds, or 741 tonnes of official gold purchases were unreported in 2022. According to analysts, unreported gold purchases are likely to have come from countries like China and Russia, who are looking to de-dollarize global trade to circumvent Western sanctions.