For example, a survey of small-business owners found that 51% did not believe they could survive the pandemic for longer than three months. At the same time, the S&P 500 posted its worst first-quarter on record. In response to this havoc, the U.S. Federal Reserve (the Fed) is taking unprecedented steps to try and stabilize the economy. This includes a return to quantitative easing (QE), a controversial policy which involves adding more money into the banking system. To help us understand the implications of these actions, today’s chart illustrates the swelling balance sheet of the Fed.

How Does Quantitative Easing Work?

Expansionary monetary policies are used by central banks to foster economic growth by increasing the money supply and lowering interest rates. These mechanisms will, in theory, stimulate business investment as well as consumer spending. However, in the current low interest-rate environment, the effectiveness of such policies is diminished. When short-term rates are already so close to zero, reducing them further will have little impact. To overcome this dilemma in 2008, central banks began experimenting with the unconventional monetary policy of QE to inject new money into the system by purchasing massive quantities of longer-term assets such as Treasury bonds. These purchases are intended to increase the money supply while decreasing the supply of the longer-term assets. In theory, this should put upward pressure on these assets’ prices (due to less supply) and decrease their yield (interest rates have an inverse relationship with bond prices).

Navigating Uncharted Waters

QE falls under intense scrutiny due to a lack of empirical evidence so far. Japan, known for its willingness to try unconventional monetary policies, was the first to try QE. Used to combat deflation in the early 2000s, Japan’s QE program was relatively small in scale, and saw mediocre results. Fast forward to today, and QE is quickly becoming a cornerstone of the Fed’s policy toolkit. Over a span of just 12 years, QE programs have led to a Fed balance sheet of over $6 trillion, leaving some people with more questions than answers. Kevin Logan, Chief Economist at HSBC Critics of QE cite several dangers associated with “printing” trillions of dollars. Increasing the money supply can drive high inflation (though this has yet to be seen), while exceedingly low interest rates can encourage abnormal levels of consumer and business debt. On the other hand, proponents will maintain that QE1 was successful in mitigating the fallout of the 2008 financial crisis. Some studies have also concluded that QE programs have reduced the 10-year yield in the U.S. by roughly 1.2 percentage points, thus serving their intended purpose. Joseph E. Gagnon, Senior Fellow at the Peterson Institute for International Economics Regardless of which side one takes, it’s clear there’s much more to learn about QE, especially in times of economic stress.

The Other Exponential Curve

When conducting QE, the securities the Fed buys make their way onto its balance sheet. Below we’ll look at how the Fed’s balance sheet has grown cumulatively with each iteration of QE:

QE1: $2.3 Trillion in Assets The Fed’s first QE program ran from January 2009 to August 2010. The cornerstone of this program was the purchase of $1.25 trillion in mortgage-backed securities (MBS). QE2: $2.9 Trillion in Assets The second QE program ran from November 2010 to June 2011, and included purchases of $600B in longer-term Treasury securities. Operation Twist (Maturity Extension Program) To further decrease long-term rates, the Fed used the proceeds from its maturing short-term Treasury bills to purchase longer-term assets. These purchases, known as Operation Twist, did not expand the Fed’s balance sheet, and were concluded in December 2012. QE3: $4.5 Trillion in Assets Beginning in September 2012, the Fed began purchasing MBS at a rate of $40B/month. In January 2013, this was supplemented with the purchase of long-term Treasury securities at a rate of $45B/month. Both programs were concluded in October 2014. Balance Sheet Normalization Program: $3.7 Trillion in Assets The Fed began to wind-down its balance sheet in October 2017. Starting at an initial rate of $10B/month, the program called for a $10B/month increase every quarter, until a final reduction rate of $50B/month was reached. QE4: $6 Trillion and Counting In October 2019, the Fed began purchasing Treasury bills at a rate of $60B/month to ease liquidity issues in overnight lending markets. While not officially a QE program, these purchases still affect the Fed’s balance sheet.

After the COVID-19 pandemic hit U.S. shores, however, the Fed pulled out all the stops. It cut its target interest rate to zero for the first time ever, injected $1.5 trillion into the economy (with more stimulus to come), and reduced the overnight reserve requirement to zero. Despite receiving little attention in the media, this third measure may be the most significant. For protection against bank runs, U.S. banks have historically been required to hold 10% of their liabilities in cash reserves. Under QE4, this requirement no longer stands.

No End in Sight

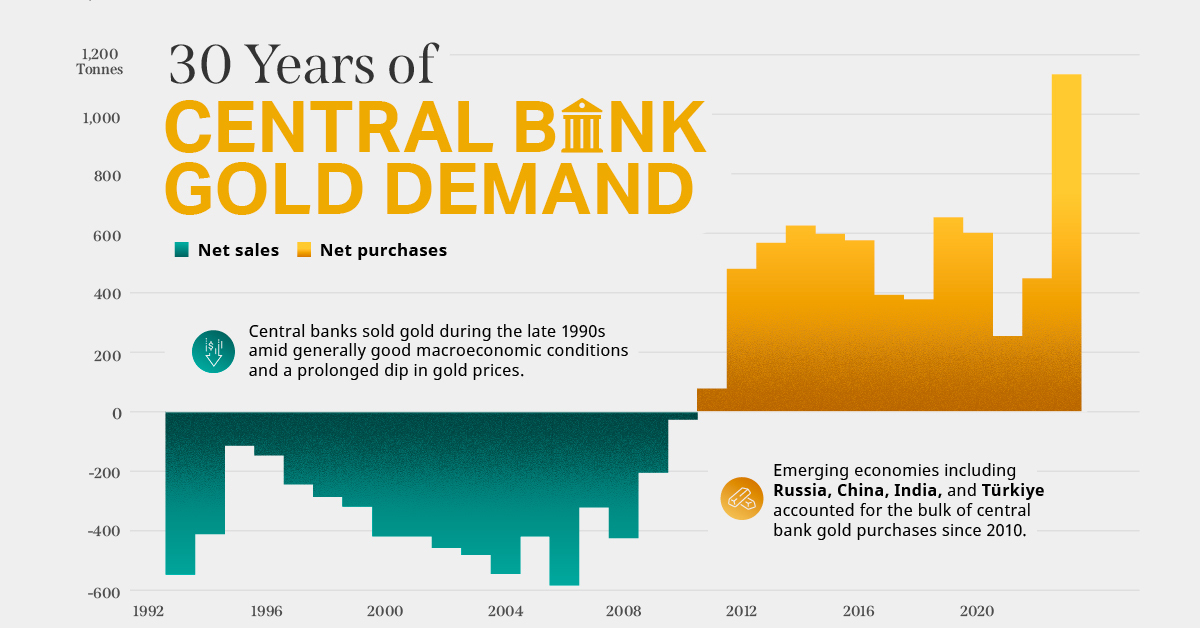

Now that the Fed is undertaking its most aggressive QE program yet, it’s a tough guess as to when equilibrium will return, if ever. After nearly two years of draw-downs, Fed assets fell by just $0.7 trillion—in a matter of weeks, however, this progress was completely retraced. QE4 is showing that what goes up, may not necessarily come down. on Did you know that nearly one-fifth of all the gold ever mined is held by central banks? Besides investors and jewelry consumers, central banks are a major source of gold demand. In fact, in 2022, central banks snapped up gold at the fastest pace since 1967. However, the record gold purchases of 2022 are in stark contrast to the 1990s and early 2000s, when central banks were net sellers of gold. The above infographic uses data from the World Gold Council to show 30 years of central bank gold demand, highlighting how official attitudes toward gold have changed in the last 30 years.

Why Do Central Banks Buy Gold?

Gold plays an important role in the financial reserves of numerous nations. Here are three of the reasons why central banks hold gold:

Balancing foreign exchange reserves Central banks have long held gold as part of their reserves to manage risk from currency holdings and to promote stability during economic turmoil. Hedging against fiat currencies Gold offers a hedge against the eroding purchasing power of currencies (mainly the U.S. dollar) due to inflation. Diversifying portfolios Gold has an inverse correlation with the U.S. dollar. When the dollar falls in value, gold prices tend to rise, protecting central banks from volatility. The Switch from Selling to Buying In the 1990s and early 2000s, central banks were net sellers of gold. There were several reasons behind the selling, including good macroeconomic conditions and a downward trend in gold prices. Due to strong economic growth, gold’s safe-haven properties were less valuable, and low returns made it unattractive as an investment. Central bank attitudes toward gold started changing following the 1997 Asian financial crisis and then later, the 2007–08 financial crisis. Since 2010, central banks have been net buyers of gold on an annual basis. Here’s a look at the 10 largest official buyers of gold from the end of 1999 to end of 2021: Rank CountryAmount of Gold Bought (tonnes)% of All Buying #1🇷🇺 Russia 1,88828% #2🇨🇳 China 1,55223% #3🇹🇷 Türkiye 5418% #4🇮🇳 India 3956% #5🇰🇿 Kazakhstan 3455% #6🇺🇿 Uzbekistan 3115% #7🇸🇦 Saudi Arabia 1803% #8🇹🇭 Thailand 1682% #9🇵🇱 Poland1282% #10🇲🇽 Mexico 1152% Total5,62384% Source: IMF The top 10 official buyers of gold between end-1999 and end-2021 represent 84% of all the gold bought by central banks during this period. Russia and China—arguably the United States’ top geopolitical rivals—have been the largest gold buyers over the last two decades. Russia, in particular, accelerated its gold purchases after being hit by Western sanctions following its annexation of Crimea in 2014. Interestingly, the majority of nations on the above list are emerging economies. These countries have likely been stockpiling gold to hedge against financial and geopolitical risks affecting currencies, primarily the U.S. dollar. Meanwhile, European nations including Switzerland, France, Netherlands, and the UK were the largest sellers of gold between 1999 and 2021, under the Central Bank Gold Agreement (CBGA) framework. Which Central Banks Bought Gold in 2022? In 2022, central banks bought a record 1,136 tonnes of gold, worth around $70 billion. Country2022 Gold Purchases (tonnes)% of Total 🇹🇷 Türkiye14813% 🇨🇳 China 625% 🇪🇬 Egypt 474% 🇶🇦 Qatar333% 🇮🇶 Iraq 343% 🇮🇳 India 333% 🇦🇪 UAE 252% 🇰🇬 Kyrgyzstan 61% 🇹🇯 Tajikistan 40.4% 🇪🇨 Ecuador 30.3% 🌍 Unreported 74165% Total1,136100% Türkiye, experiencing 86% year-over-year inflation as of October 2022, was the largest buyer, adding 148 tonnes to its reserves. China continued its gold-buying spree with 62 tonnes added in the months of November and December, amid rising geopolitical tensions with the United States. Overall, emerging markets continued the trend that started in the 2000s, accounting for the bulk of gold purchases. Meanwhile, a significant two-thirds, or 741 tonnes of official gold purchases were unreported in 2022. According to analysts, unreported gold purchases are likely to have come from countries like China and Russia, who are looking to de-dollarize global trade to circumvent Western sanctions.

There were several reasons behind the selling, including good macroeconomic conditions and a downward trend in gold prices. Due to strong economic growth, gold’s safe-haven properties were less valuable, and low returns made it unattractive as an investment.

Central bank attitudes toward gold started changing following the 1997 Asian financial crisis and then later, the 2007–08 financial crisis. Since 2010, central banks have been net buyers of gold on an annual basis.

Here’s a look at the 10 largest official buyers of gold from the end of 1999 to end of 2021:

Source: IMF

The top 10 official buyers of gold between end-1999 and end-2021 represent 84% of all the gold bought by central banks during this period.

Russia and China—arguably the United States’ top geopolitical rivals—have been the largest gold buyers over the last two decades. Russia, in particular, accelerated its gold purchases after being hit by Western sanctions following its annexation of Crimea in 2014.

Interestingly, the majority of nations on the above list are emerging economies. These countries have likely been stockpiling gold to hedge against financial and geopolitical risks affecting currencies, primarily the U.S. dollar.

Meanwhile, European nations including Switzerland, France, Netherlands, and the UK were the largest sellers of gold between 1999 and 2021, under the Central Bank Gold Agreement (CBGA) framework.

Which Central Banks Bought Gold in 2022?

In 2022, central banks bought a record 1,136 tonnes of gold, worth around $70 billion. Türkiye, experiencing 86% year-over-year inflation as of October 2022, was the largest buyer, adding 148 tonnes to its reserves. China continued its gold-buying spree with 62 tonnes added in the months of November and December, amid rising geopolitical tensions with the United States. Overall, emerging markets continued the trend that started in the 2000s, accounting for the bulk of gold purchases. Meanwhile, a significant two-thirds, or 741 tonnes of official gold purchases were unreported in 2022. According to analysts, unreported gold purchases are likely to have come from countries like China and Russia, who are looking to de-dollarize global trade to circumvent Western sanctions.