With many countries and regions pledging to move away from fossil fuels and towards cleaner sources of energy, the overall energy mix is becoming more diversified. But shutting down plants and replacing them with new sources takes time, and most countries are still incredibly reliant on fossil fuels. This video from James Eagle uses data from BP’s Statistical Review of World Energy to examine how the energy mix of G20 members has changed from 1965 to 2019.

G20’s Energy History: Fossil Fuel Dependence (1965–1999)

At first, there was oil and coal. From the 1960s to the 1980s, energy consumption in the G20 countries relied almost entirely on these two fossil fuels. They were the cheapest and most efficient sources of energy for most, though some countries also used a lot of natural gas, like the United States, Mexico, and Russia. But the use of oil for energy started to decrease, beginning most notably in the 1980s. Rocketing oil prices forced many utilities to turn to coal and natural gas (which were becoming cheaper), while others in countries like France, Japan, and the U.S. embraced the rise of nuclear power. This is most notable in countries with high historic oil consumption, like Argentina and Indonesia. In 1965, these three countries relied on oil for more than 83% of energy, but by 1999, oil made up just 55% of Indonesia’s energy mix and 36% of Argentina’s. Even Saudi Arabia, the world’s largest oil exporter, began to utilize oil less. By 1999, oil was used for 65% of energy in the country, down from a 1965 high of 97%.

G20’s Energy Mix: Gas and Renewables Climb (2000–2019)

The conversation around energy changed in the 21st century. Before, countries were focused primarily on efficiency and cost, but very quickly, they had to start contending with emissions. Climate change was already on everyone’s radar. The UN Framework Convention on Climate Change was signed in 1992, and the resulting Kyoto Protocol aimed at reducing greenhouse gas emissions was signed in 1997. But when the Kyoto Protocol went into effect in 2005, countries had very different options available to them. Some started to lean more heavily on hydroelectricity, though countries that already utilized them like Canada and Brazil had to look elsewhere. Others turned to nuclear power, but the 2011 Fukushima nuclear disaster in Japan turned many away. This is the period of time that renewables started to pick up steam, primarily in the form of wind power at first. By 2019, the G20 members that relied on renewables the most were Brazil (16%), Germany (16%), and the UK (14%). However, the need to reduce emissions quickly made many countries make a simpler switch: cut back on oil and coal and utilize more natural gas. Bituminous coal, one of the most commonly used in steam-electric power stations, emits 76% more CO₂ than natural gas. Diesel fuel and heating oil used in oil power plants emit 38% more CO₂ than natural gas. As countries begin to push more strongly towards a carbon-neutral future, the energy mix of the 2020s and onward will continue to change. on Cities—settlements that are densely populated and self-administered—require many specific prerequisites to come into existence. The most crucial, especially for much of human history, is an abundance of food. Surplus food production leads to denser populations and allows for people to specialize in other skills that are not associated with basic human survival. But that also means that cities usually consume more primary goods than they produce. And their size requires a host of many other services—such as transport and sanitation—that are traditionally expensive to maintain. So maintaining large urban centers, and especially the world’s largest cities, was a monumental task. Mapper and history YouTuber Ollie Bye has visualized the seven largest cities in the world since 3,000 BCE. His video covers cities with a minimum population of 10,000 and hints at historical events which led to the establishment, growth, and eventual fall of cities.

The World’s Largest City Throughout History

With any historical data, accuracy is always a concern, and urban populations were rough and infrequent estimates up until the Industrial Revolution. Bye has used a variety of data sources—including the UN and many research papers—to create the dataset used in the video. In some places he also had to rely on his own estimates and criteria to keep the data reasonable and consistent:

In early history, some cities didn’t have given population estimates for long periods of time, and had to be equalized or estimated through other sources. For example, Babylon had a population estimate at 1,600 BCE (60,000) and at 1,200 BCE (75,000) but none in the 400 years between. Cities that only briefly climbed above a population of 10,000, or that would have made the largest cities ranking for only a couple of years (and based on uncertain estimates), were not included.

Here’s a look at the largest city starting from the year 3,000 BCE, with populations listed in millions during the last year of each city’s “reign.” Cities are also listed with the flags of current-day countries in the same location.

Ancient Cities in the Fertile Crescent

Considered the “cradle of civilization,” the Fertile Crescent in the Middle East was home to all seven of the largest cities in the world in 3,000 BCE. The Sumerian city of Uruk (modern-day Iraq), allegedly home to the legendary king Gilgamesh, topped the list with 40,000 people. It was followed by Memphis (Egypt) with 20,000 inhabitants. For the next 1,700 years, other Mesopotamian cities in modern-day Iraq and Syria held pole positions, growing steadily and shuffling between themselves as the largest. 2,250 BCE marked the first time a different Asian city—Mohenjo-Daro (modern-day Pakistan) from the Indus Valley Civilization—found a spot at #4 with 40,000 people. The table below is a quick snapshot of the seven largest cities in the world for from 3,000 BCE to 200 CE. Again, populations are listed in millions. It wasn’t until 1,250 BCE that the top two spots were taken by cities in different regions: Pi-Ramesses (Egypt) and Yin (China), both with more than 100,000 residents. Egyptian cities would continue to be the most populous for the next millennium—briefly interrupted by Carthage and Babylon—until the start of the Common Era. By 30 CE, Alexandria was the largest city in the world, but the top 10 had representatives from the Middle East, Northern Africa, and Asia.

All Roads Lead to Rome

One city in Europe meanwhile, was also beginning to see steady growth—Rome. It took until halfway through the 3rd century C.E. for Rome to become the most populous city, followed closely still by Alexandria (Egypt). Meanwhile in Iraq, Ctesiphon, the capital of the Sasanian empire was growing rapidly. Towards the end of the 3rd century, the Roman empire was divided into two, with Constantinople becoming the new capital for the Eastern half. Consequently, it had outgrown Rome by 353 and become the world’s most populous city, and for the next few centuries would reclaim this title time and time again.

The Largest Cities Reach 1 Million

In the 9th century, Baghdad became the first city to have 1 million residents (though historians also estimate Rome and the Chinese city of Chang’an may have achieved that figure earlier). It would be nearly nine centuries until a city had one million inhabitants again, and Baghdad’s reign didn’t last long. By the 10th century, Bian, the capital of the Northern Song dynasty in China, had become the largest city in the world, with Baghdad suffering from relocations and shifting political power to other cities in the region. From the 12th century onwards, Mongol invasions in the Middle East and Central Asia severely limited population growth in the region. European cities too were ravaged in the 14th century, but by plagues instead of marauders. For the next few hundred years, Cairo (Egypt), Hangzhou (China), and Vijayanagara (India) would top the list until Beijing took (and mostly held onto) the top spot through the 19th century.

Industrial Revolution and Rapid Urbanization

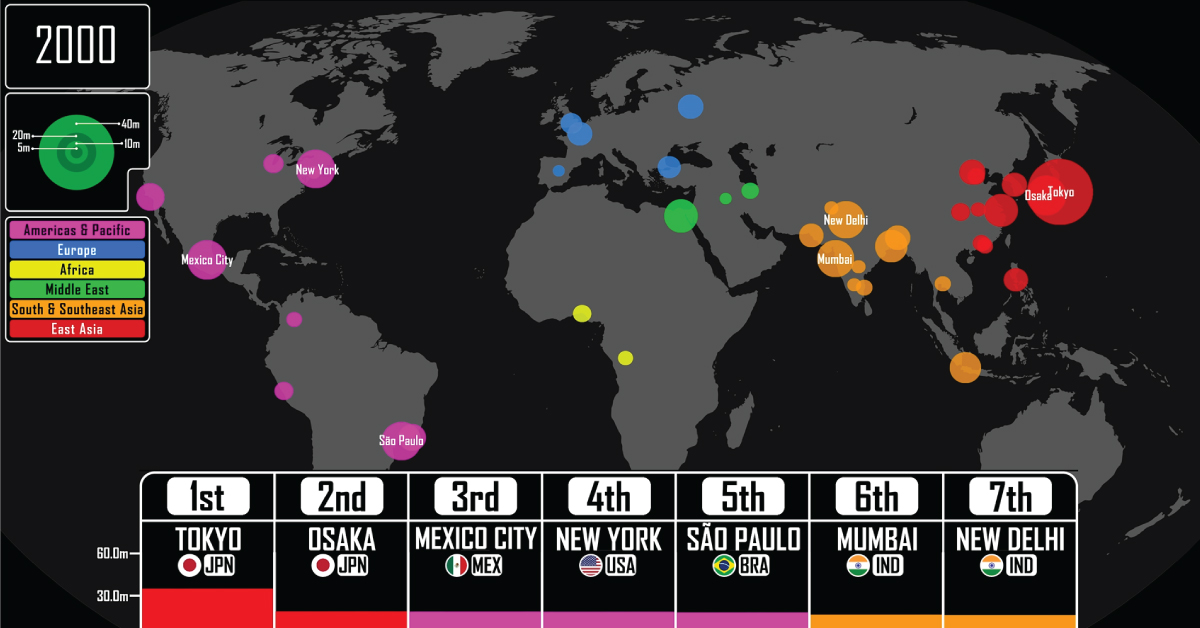

The start of the Industrial Revolution in the UK—spreading to the rest of Europe and later on the U.S.—led to hitherto unseen levels of urban population growth. Factories needed labor, which caused mass emigration from the rural countryside to urban centers of growth. In 1827, London passed Beijing to become the largest city in the world with 1.3 million residents. Over the next 100 years, its population increased nearly 7 times, remaining the most populous city until the end of World War I, by which time it was overtaken by New York. From 1920 to 2022, the world population quadrupled thanks to improvements in farming and healthcare, and cities saw rapid growth as well. The beginning of the 20st century saw the top 10 largest cities in the world in the U.S., Europe, and Japan. By the 21st century however, growth shifted away to other parts of the world and by 2021, the top seven had cities only from Asia and the Americas. Tokyo, which took the top spot in 1954, is the largest city in the world today with a population of 37 million (including the entire metropolitan area). It is followed by New Delhi with 31 million, but by 2028, the UN estimates that positions will switch on the leaderboard and New Delhi will overtake Tokyo.

What Does Population Growth Say About the Past (and Future)?

The rise and fall of cities through the sands of time can give us insight into the trajectory of civilization growth. As civilizations grow, become richer, and reach their zenith, so too do their cities blossom in tandem. For example, of the modern-day seven largest cities in the world, four of them belong to countries with the 10 largest economies in the world. Meanwhile, sudden falls in urban population point to turbulence—political instability, wars, natural disasters, or disease. Most recently Ukraine’s cities are seeing depopulation as residents flee conflict zones, raising the specter of a demographic crisis for the country should the war continue. Thus, tracking the size of urban population can help policymakers forecast future roadblocks to growth, especially when prioritizing sustainable growth for a country.